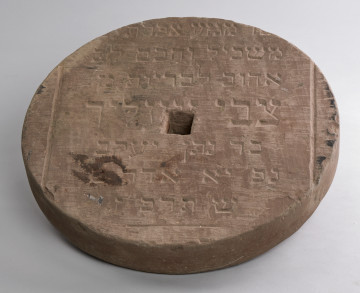

The grinding wheel

non ante 1939

Museum of the history of Polish Jews

Part of the collection: Objects made of matzevot

The fragment of a tombstone (stele) is a gift from Barbara and Jacek Redzisz. The matzevah has a hollow as it was turned into a grinding wheel; numerous surface damages are visible. Unfortunately, we do not know the history of this particular matzevah, we do not know from which cemetery it was taken. We only know that the matzeva is dedicated to a woman: [...] A pure woman | Virtuous and respectable [reading uncertain - ed.] [...]. Due to the deformation of the tombstone, the fragment with the name and surname of the deceased has not survived.

The form of Jewish tombstones derives from antiquity, where it marked sacred pillars, in Canaanite sanctuaries (https://delet.jhi.pl/pl/psj?articleId=15427, access date: 16 November 2021). A gravestone was placed at the head or in the legs of a deceased person. The tombstone was oriented towards the east, and the epitaph (grave inscription) was placed on the eastern side of the slab (for more on this topic: https://delet.jhi.pl/pl/psj?articleId=15462, date of access: 16 November 2021). An essential part is the epitaph, which since the 19th century has taken the form of a kind of emanation, a sign of identification with a particular culture. This phenomenon intensified especially during the period of popularity of the assimilation movement (for more on assimilation in the 19th century see: A. Jagodzińska, Pomiędzy. Akulturacja Żydów Warszawy w drugiej połowie XIX wieku (Between. Acculturation of the Jews of Warsaw in the2nd Half of the 19th Century), Wrocław 2008). From the 16th century onwards, symbols reflecting the merits, life and personality of the deceased began to be placed above the epitaph. We can only guess what was depicted on it. Symbols characteristic for women are first of all a candlestick, usually depicted with candles, signifying piety - observance of the obligation to light and bless the Sabbath lights (sometimes hands were placed next to the candles). A frequent motif on the gravestones of women is also a bird with a chick or a bird feeding a chick - symbols of family life and maternal love.

Interestingly, surnames were very rare on traditional Jewish tombstones. The identity of the deceased was determined by family relationships: e.g. daughter, mother, son.The end of a gravestone inscription usually includes the sentence: May his soul be incorporated into the wreath of eternal life. (often in abbreviated form) - a reference to the Book of Samuel 25:29. Sometimes the ending is a phrase that is uttered when the corpse is laid to rest: And thou shalt go thy way, until the end come, and thou shalt rest, and arise to thy lot at the end of days.The subject of symbolism on Jewish tombstones is extremely wide and varied; for more on it: https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/slownik/symbolika-nagrobkow.

Desecration of matzevot by converting them into objects of everyday use has a long history. A discussion on the subject was sparked by a photographic exhibition by Łukasz Baksik, and later by the publication of a book, also by this author, Macewy codziennego użytku (Matzevot of Everyday Use) in 2013, where he talks about and gives space to photographs showing matzevot as paving slabs, material for hardening roads, or grinding wheels.

It was the grinding wheel that the matzeva donated to the museum was converted into. Research on Jewish cemeteries shows that this was not an isolated post-war practice. In his monograph, Krzysztof Bielawski gives voice to the inhabitants of Radziłów (a town that was part of the wave of pogroms against the Jewish population that occurred in the summer of 1941) who recall: They used to take tiles for wheelbarrows to sharpen their axes [...], I don't think there was anyone in Radziłów who didn't have wheelbarrows made of these cemetery stones. [When people started to rebuild, they took gravel on wheelbarrows [...] And the new people's government built a piece of road from the remains which peasants did not steal at night. [The stones from the barn are in the foundation of our house, everyone took one. [...]. The wheelbarrows mentioned in the text are grinding wheels. The features of sandstone contributed to the fact that matzevot after being processed - a circle cut out of a slab, a square hole punched in its central part and mounted on an axle with a crank - were very often used as grinding wheels. See K. Bielawski, Zagłada cmentarzy żydowskich (Destruction of Jewish cemeteries), Warsaw 2020, pp. 129-130.

Natalia Różańska

Author / creator

Dimensions

cały obiekt: height: 9 cm, width: 40 cm, diameter: 40 cm

Creation time / dating

Creation / finding place

Owner

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

Identification number

Location / status

non ante 1939

Museum of the history of Polish Jews

2003

Museum of the history of Polish Jews

2003

Museum of the history of Polish Jews

DISCOVER this TOPIC

Castle Museum in Łańcut

DISCOVER this PATH

Educational path