The photograph of Emilia Leibel from the period shortly after her repatriation

ca 1946

Museum of the history of Polish Jews

Memorabilia of Emilia Leibel, donated to the collection by Prof. Maria Kłańska, who recorded and compiled an interview with Emilia Leibel, published under the title Wspomnienia Żydowka krakowskiej (Memories of a Jewish Woman from Kraków). The memorabilia consist of documents and photographs used in the publication (published by the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, Kraków 2010; this book and the oral history interview, see https://www.centropa.org/biography/emilia-leibel, accessed 17 November 2021 - are the primary sources for the content of this note). Emilia (Misia, Mirl) née Grossbart, married name Leibel (1911-2008), grew up in Łagiewniki, at the beginning of the 20th century a village near Kraków (now within Kraków). Her great-grandparents' magnificent brick building with farm buildings was situated opposite the convent of the Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy (now part of the Divine Mercy Sanctuary). For generations, the Grossbarts had been involved in the purchase of cattle skins, and they also cultivated the land, employing hired workers. The Grossbarts' fields stretched as far as the River Wilga. They were a traditional Jewish family, where religious observance and kosher food were observed, with grandfather wearing a black hat and grandmother a wig. Emilia's father, Benzion Grossbart, had five sisters. He received a home education and took his exams in Vienna. Her mother, Ernestyna, with the Jewish name Ester Hadasa, came from a related family from Dębica (the Leibels), also with many children: she had three brothers and four sisters. Ernestyna Leibel took care of the house.

When Emilia turned five, in order to be able to start school she moved with her parents and two years older brother Jehuda to a rented one-room flat at 19 Krakusa Street in Pogórze (with a shared toilet in the courtyard). Emilia Grossbart attended the Queen Kinga public school in Józefińska Street, and her brother, who had a disabled leg, attended a small private Evangelical school in Grodzka Street. It was the time of the First World War, and her father was conscripted into the Austrian army; after a short stay in the barracks, he was sent to serve in Cracow.

The family moved to a three-room flat at 6 Czarnieckiego Street (with its own bathroom) when Emilia was 11 years old. At that time, Emilia and Jehuda began attending the Hebrew gymnasium at Flat 10, 8 Podbrzezie Street. In the fifth year of middle school, Jehuda did not survive the appendectomy operation. After the death of his son, the father broke down, a business partner took advantage of the difficult situation and the Grossbart family lost all their possessions. The daughter, in order to partially cover the costs of her own education, gave private lessons (in secret from her father). After graduating from high school she attended business courses and in the following year began university studies (Polish Philology). She did not complete her studies, however, because in 1933 she married Juliusz Leibel, her distant cousin, 15 years older, a wealthy leather exporter from Kalwaria Zebrzydowska. The Leibels lived there, in a rented two-room flat by the market square. Their daughter, Halina Leibel, was born in 1934.

In the summer of 1939, faced with the risk of war, Juliusz Leibel's family moved closer to the south-eastern borders of the country (to Jarosław), including Emilia and Halina. At the beginning of September, they were joined by Juliusz Leibel; eventually, the whole family ended up in Lviv, an area occupied by the Soviet Union.

In the spring of 1940, the NKVD came for Juliusz and Emilia Leibel with an order to deport them. As their husband's brother Henryk was staying with them overnight, they took him too. While the Leibels were waiting for the train at the station, they were voluntarily joined by Anna and Markus Leibel, Juliusz's parents, as well as his sister Giza Krüger and her grown-up daughter Irena (then already a student at Lviv University). They travelled by train for about three weeks to a port on the Volga, from where they sailed to the town of Koźmodiemiansk, and from there they were driven another 35 km or so deep into the forest on the territory of the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (now the Republic of Mari El, an autonomous republic of the Russian Federation). They occupied a wooden house, the men and young women worked at logging, and Emilia Leibel initially looked after her child and grandparents. She soon managed to get a job in a factory producing malt extract, then she was sent to work in a mill. Juliusz Leibel did not survive the very hard work in the forest and died in the early spring of 1944.

During their exile, the family corresponded with their second son, Juliusz's and Giza's brother, as well as with Giza Krüger's husband, both of whom were in the oflag. Irena was arrested because of this correspondence. The Soviets claimed that since her father was a Jewish officer and still alive, he was certainly spying for Germany. There was even a trial for Irena Krüger, which in similar situations ended in a sentence of hanging - fortunately, the war ended earlier than the trial and the woman was released.

The Union of Polish Patriots organised a school for Polish children in Kozmodemyansk. Most of them were of Jewish origin. Emilia Leibel taught in the early grades, and a professional teacher from Lviv continued teaching in the older grades. Halina Leibel also started attending the school.

In 1946, Emilia Leibel obtained certification of Polish citizenship - on the basis of a driving licence (in Lviv the Leibels destroyed their passports because they were stamped with foreign visas - they were afraid that this might arouse the suspicions of the Soviet authorities). She and her daughter reached Kraków by freight car.

Thanks to a young boy she met accidentally from Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, who remembered the Leibels from before the war, Emilia Leibel contacted Mala Rubinstein, the founder of the first Jewish educational institution in pre-war Kraków. Rubinstein helped to place Halina there and employed Emilia Leibel. Soon, over 80 children arrived from the Soviet Union and an orphanage was set up in a four-storey building on what is now Chmielowskiego Street.

Emilia Leibel registered with the Jewish community. She was asked to witness at the wedding of a man who no longer had any living family. He turned out to be her uncle's brother. He soon left for Israel.

At the beginning of the 1950s, Emilia Leibel had a chance to work at the Ministry of Education in Warsaw and to get a flat there. Her daughter, Halina, who was in her final year of secondary school, tried to study at the High School of Booksellers in Warsaw, but after a month of studying and living at a boarding house, she returned to Krakow. She dropped out of school and started working in Nowa Huta. Both she and her mother therefore remained in Kraków.

Because Emilia Leibel corresponded with friends who had ended up in Israel (including the aforementioned cousin), and because she had never been a communist, after five years at the orphanage she was dismissed on the pretext of smuggling children into Israel. She found employment with the Society of Friends of Children (https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo/Towarzystwo-Przyjaciol-Dzieci;3988455.html, accessed 17 November 2021), where she worked for three years. She was dismissed for refusing to remove crosses in schools.

After many years of effort, she finally received a cooperative flat in Kazimierza Wielkiego Street. Thanks to the sale of her in-laws' house in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, she could go on a trip to Israel.

She got a job at the Vocational Training Centre, and then at the Polish Economic Society, which was separated from ZDZ, until she was dismissed at the end of the 1960s. She then returned to work at ZDZ, as a part-time librarian. When the library was closed, she worked in the afternoons enrolling students in courses.

During the Solidarity era she was encouraged to join the union, but refused. It was soon suggested that she retire. Six months later, she was asked to return to work, but she decided not to - because of her age (she was already almost 70), but above all, she was overcome with honour.

The pupils of the orphanage remembered her even after many years, calling and sending postcards.

Ewa Małkowska-Bieniek

Znaleziono 16 obiektów

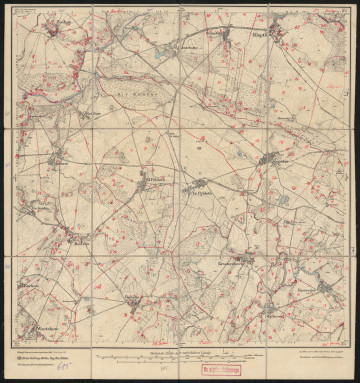

1876

National Museum in Szczecin

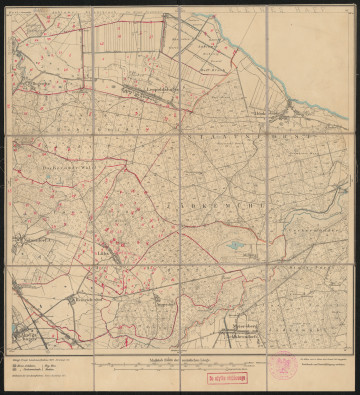

1925 — 1939

National Museum in Szczecin

1936

National Museum in Szczecin

DISCOVER this TOPIC

National Museum in Lublin

DISCOVER this PATH

Educational path