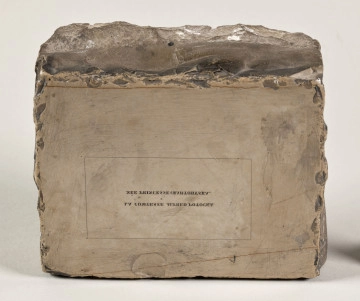

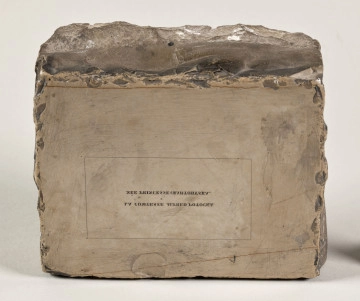

Paperweight

XIX century

Castle Museum in Łańcut

Part of the collection: Weapons, music instruments, varia

Human memory is unreliable, it is better to write down your thoughts so that they do not fly away. Writing is an art that is one of the milestones of human civilization.

All you need to write is a blank sheet of paper, a pen, ink (increasingly replaced by word processors, mice, etc.) and you can create the next national epic. To make it not too easy, the ink stains the sheets of paper, stains the fingers, but tissue paper can remedy this. Once we have dealt with the ink and stains, we sit down and "pour" our thoughts onto paper. We're sitting, we're writing with enthusiasm, and then someone walks in the room, opens the door, opens the window, and this treacherous wind blows the written and unwritten pages to the floor, mixing everything up. The poor creator had to pick them up, often on his knees, and his back hurts from sitting. When he has already collected the pages, it turns out that they are mixed up, and he forgot to number them and, to make matters worse, a few pages were forgotten during the collection and in fact they should be rewritten. Finally, we manage to put the written pages in order and we sit down to continue our work, and then someone comes in again on an urgent matter, someone opens the second window and again we have confetti from our written pages and we start collecting our written "golden thoughts" from the beginning. After a few such visits, we forget our own thoughts, discouragement creeps in, and because of such a small zephyr, some "epoch-making" work may not be created. And yet it was enough (with the exception of locking the doors and windows) to hold the blank and written pages with some heavy object, but not so heavy as to destroy the sheets of paper. Such an object is a paperweight, which is sometimes a small work of art in the form of a figurine, a plaque made of alabaster or glass, or other materials that are pleasing to the eye. They can also be very simple elements, such as various types of stones collected during trips to places sentimentally close to the collectors or related to the history of family or country. In this way, the paperweight became an indispensable desk equipment next to the inkwell, pounce pot, tissue paper, pen holder, lamp, and just like them, it took on different forms and shapes depending on the fashion prevailing in art at a given period. Paperweights, thanks to their form/shape and the material they are made of, complement the décor of the desk – those made of wood evoke the impression of warmth, those made of metal, especially precious metals, add majesty, and those made of glass or crystal, thanks to reflections, give the character of ephemerality like written thoughts. The most ordinary ones in the form of stones remind us of the places we have been to. They can also remind us of past centuries and events that determine our history and heritage.

The discussed paperweights from the collection of the Museum – Castle in Łańcut come from the collection of the Potocki family, belong to the latter category and come from places currently outside the country (Borderlands) related to the history of Poland. One of them is the paperweight with the inv. No. S.4480MŁ. It in the shape of a lying stone irregular cuboid with polished sides and a wall with a plaque, on the top it has a round brass handle mounted from the same material is made an elongated decorative plate decorated with a shell motif, attached to a stone without visible studs and with the inscription "Trembowla - 1870". Like most of the towns and castles of the former south-eastern Poland, now called Eastern Borderlands, it is closely related to the history of our homeland. The inhabitants of Trembowla derive the name of the town from the Old Russian word "tierebiti" meaning "to grub up", which is the most reasonable explanation given the large forestation of the area. Information about the first settlement dates back to the 11th century, when it was the capital of the Terebovlia principality, which makes this settlement one of the oldest in the Galician region. The importance of the settlement and most probably the castle declined when the seat of the prince was moved to Halicz (1142). In the forties of the fourteenth century, the owner of the castle became the Polish king Casimir the Great, which is mentioned in the chronicles of Janek of Czarnolas and Jan Długosz. The times of the Jagiellonians brought the development of both the city and the fortress. In those times the city was given the Magdeburg law. Constant wars and unrest (1498 invasion of the Moldavian Hospodar Stephen III, 1515, invasion of the Tatars on the land of Galicia) caused the destruction of the settlement, the castle itself also suffered. In 1534, a new castle was erected on the request of the castellan of Cracow, Andrzej Tęczyński, and further efforts to increase the defensive value of the castle were made by the district governor Aleksander Bałaban.

In the construction of the castle, the natural terrain was used and a large brick fortress was erected on the castle hill. The castle was built on the plan of an elongated triangle on a hill, on the fork of the Gniezno River and the Peczenia stream, a large bastion was built, equipped with artillery, which could control the valley with the town buildings with its fire. The wars with Ottoman Empire in the seventies of the 17th century were marked by varying luck for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, apart from great victories (1672 the Second Battle of Chocim) there were also defeats, such as the fall of Kamieniec Podolski and smaller borderland fortresses. The year 1675 brought another invasion of the Turkish army (the army commanded by Ibrahim Shishman numbered 30,000), supported by the Tatars, who occupied the castle in Zbaraż without a fight, captured the castle in Podhajce and on September 20, 1675, with the strength of 10,000 soldiers, stood at Trembowla. The defending forces were ridiculously small (compared to the Turks) because they consisted of 80 infantry soldiers supported by nobles from the surrounding lands and about 200 townspeople and peasants from the surrounding area. After refusing to surrender the fortress, the Ottoman army began assaults under the cover of heavy artillery fire, which, despite their intensity, were unsuccessful, especially since the walls were up to 4 m thick. The Turkish army also had specialized units, today called sappers, which specialized in digging tunnels for the walls of besieged fortresses and placing strong explosives there. Such mines, detonated in sensitive places, usually caused the collapse of part of the defensive walls or the formation of a breach through which masses of Turkish infantry penetrated, which led to the slaughter of the defenders and the fall of the fortress. Thus, after unsuccessful assaults, tunnels were dug in the direction of the castle walls, which did not escape the attention of the defenders, some of whom began to consider surrendering the fortress and putting themselves at the mercy of the enemy. The commandant of the castle, Jan Samuel Chrzanowski, who was initially against the surrender, began to favour this decision, especially since the defenders suffered losses and there were problems (after the destruction of the well) with drinking water. It was then that the legend of Trembowla was born, which continues in our tradition to this day.

Upon hearing about the intention to surrender the fortress, the commander's wife, Anna Dorota Chrzanowska, armed with two daggers (in various versions these were two kitchen knives and two pistols), told her husband that in the event of surrender, she would kill her husband first, and then herself. It is difficult to say whether the threat of his wife, or her courage and determination in defending Trembowla, caused that the supporters of the surrender of the fortress were imprisoned and the fight was continued. According to reports, the brave Anna Dorota took an active part in the defence of the walls, and was even supposed to lead sorties, in one of such forays behind the walls she was wounded, which did not prevent her from continuing the fight. Tough defence, lack of success in assaults, and especially the news that the Polish army under the command of Jan Sobieski was coming to the rescue of Trembowla, resulted in the lifting of the siege on 11 October, and the withdrawal of Ibrahim Shishman's troops beyond the Dniester. The attitude of Anna Dorota Chrzanowska and the defence of the castle by Jan Samuel Chrzanowski became loud and famous in the Commonwealth as a symbol of resistance against the much more numerous armies of Ottoman Empire. As a reward, a year after the defence of the fortress in 1676, Anna Dorota and Jan Samuel Chrzanowski were ennobled, and soon afterwards a monument to the heroic defender was erected in front of the castle. The first monument did not last long and was destroyed, the next one was built in 1903 and was destroyed by the Germans in 1944, the current monument was erected in 2012. The further fate of Trembowla is the same as that of other towns in the borderlands- it was under the occupation (once Russian, once Austrian).

After Poland regained its independence in 1918, a garrison of the 9th Regiment of Lesser Poland Uhlans was established in Trembowla in order to increase the importance of the town. From 17 September 1939 Trembowla and other towns of the borderlands were under the occupation of the USSR. After June 22, 1941, the situation changed and these areas were under German occupation. From 1944 the town again was under the occupation of the USSR and now it is Ukraine.

Judging by the appearance of the paperweight, the asymmetrically placed plate with the name and handle, it can be concluded that a little more than half of the original object has survived to our times. As we can see, even such inconspicuous objects as paperweights (in our case stones) can be a part of history and they remind us of past years and people who created the history of Poland.

Przemysław Kucia

Author / creator

Object type

pamiątki

Material

stone

Creation time / dating

Creation / finding place

Owner

Muzeum - Zamek w Łańcucie

Identification number

Location / status

nieznany

XIX century

Castle Museum in Łańcut

nieznany

XIX century

Castle Museum in Łańcut

nieznany

XIX century

Castle Museum in Łańcut

DISCOVER this TOPIC

Castle Museum in Łańcut

DISCOVER this PATH

Educational path

0/500

We use cookies to make it easier for you to use our website and for statistical purposes. You can manage cookies by changing the settings of your web browser. More information in the Privacy Policy.

We use cookies to make it easier for you to use our website and for statistical purposes. You can manage cookies by changing the settings of your web browser. More information in the Privacy Policy.

Manage cookies:

This type of cookies is necessary for the website to function. You can change your browser settings to block them, but then the website will not work properly.

WYMAGANE

They are used to measure user engagement and generate statistics about the website to better understand how it is used. If you block this type of cookies, we will not be able to collect information about the use of the website and we will not be able to monitor its performance.