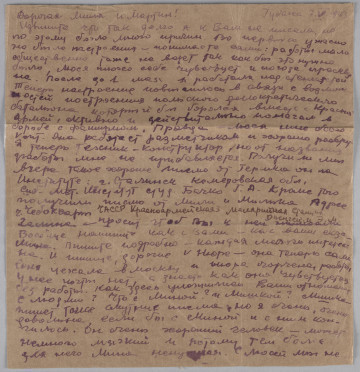

A letter

1943

Museum of the history of Polish Jews

The collection of memorabilia of Emilia Ratz contains 65 letters - mainly correspondence from the period of World War II and just after the war; letters exchanged by Emilia (née Endler) with friends during her stay in the Soviet Union and after her repatriation to Poland. This extraordinary, exceptionally voluminous document of the time shows reality - as is typical for the literature of personal document - in many contexts: social (everyday life of civilians and military men during the war and immediately after its end), historical (the letters reflect the most important events of the time, seen individually), emotional (anxiety about loved ones left in Poland; fears connected with the course of the German-Soviet war; despair when, after the German withdrawal, the scale of the Holocaust becomes apparent; hopes, also those connected with the emergence of a new political order). The appearance of the letters is noteworthy. Their materiality is also a testimony to that time - the permanent shortage of paper and the practices connected with it: the use of wrapping paper, not putting cards into envelopes but folding them, closing them in triangles. (In the transcription of the letters in Polish, the original spelling has been preserved).

Emilia née Endler Ratz was born in 1921 in Warsaw as the daughter of Izrael Endler and Maria née Katz (biographical information based mainly on oral history accounts: https://www.centropastudent.org/biography/emilia-ratz, accessed 10.10.2021). Emilia spent her childhood and early youth in a tenement house belonging to her grandfather, probably at 43 Nowolipki Street. She grew up among her father's large family and other Jewish inhabitants - only the caretaker was not Jewish at that address. Grandfather Endler ran a soap and toothpaste factory, which was located in the basement. My father distributed these goods. Emilia Ratz's mother came from Narewka in Podlasie, did not work, although she had finished secondary school and spoke three languages: Russian, Polish and German. The family occupied a small flat on the first floor, with a bathtub in the kitchen; during the day, the bathtub was covered with a board and served as a table.

As Emilia Ratz recalled, Izrael Endler obeyed religious precepts, unlike his wife. Mother sometimes failed to keep kosher; once she put a meat knife between the dairy cutlery - father immediately put the knife in the pot with the soil.

When Emilia Endler passed the so-called "little high school exam", her father decided that she was sufficiently educated and ready to marry. As a man of traditional and petit-bourgeois views, he could not understand that his daughter had rejected the attentions of a student from a rich Jewish family, whom she had met at a youth camp. In spite of everything, Emilia stood her ground and continued her education until the so-called "big matura", after which she intended to study chemistry.

When the Germans entered Warsaw, Emilia Endler insisted that the whole family escape to the east, but her father and mother did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation. Conflicted with her father, Emilia stayed with a friend with leftist convictions, Halina Altman (who later also found herself in the East; her correspondence with her constitutes the largest group of letters in this collection; see the outline of the history of Halina Altman and her family in the note to letter MPOLIN-A*.1.3). She thus put pressure on her parents to at least allow her to leave. After the Germans entered Warsaw, she was an eyewitness to the scene where one of the Jews had his beard cut off by the Germans in the market square; she saw the future in darker colours - as it turned out, more realistically than her parents. Her father did not change his mind about the escape of the whole family, but under the influence of her persuasion he accepted Emilia's departure. He hired a taxi for her and foresightedly gave her a few bars of soap for the journey; the taxi was quickly confiscated by the Germans, but the soap turned out to be very useful, serving as war "currency".

Emilia and the people she met along the way reached the border, partly on foot and partly on peasant carts, paying for food and transport with bars of soap. At the Soviet border, she was stopped by guards; after repeated unsuccessful attempts to cross, which also resulted in the loss of her jewellery, she finally managed to reach Bialystok, to her mother's brother. After a few days of nomadic life, she was exhausted and caught a cold; when she recovered, she decided, despite her uncle's protest, to go to Lwów to study, just as her father had done previously. In Lvov she began to study chemistry while working at the same time. There she met many friends from Warsaw who, like her, had taken up studies at the Lwów university. In the dean's office she also met her future husband, Marcin Ratz.

After the outbreak of the German-Soviet war, shortly before Lviv was occupied by the Germans and captured by Ukrainian nationalists, Emilia managed to escape to Tarnopol; she was soon joined by Marcin Ratz. Together they reached Dnepropetrovsk and from there by train to Stalingrad, where, in the absence of a chemistry faculty, they took up studies in mechanical engineering. Martin Ratz worked to support them and they soon married. In June 1942, they managed to leave Stalingrad for Kazakhstan, and in the autumn they arrived in Yekaterinburg (then Sverdlovsk) to continue their studies. A year later, they received their diplomas and also got a job in Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg) at an aircraft equipment factory. Although they worked twelve hours a day, the money was only enough to buy bread, tea made from dried carrots and poor quality oil.

In 1946, they arrived in Kraków (their efforts and anticipation of the possibility of going to Poland are reflected in many of their letters). Marcin Ratz's sister, Hedi (married name Reissler), lived in Kraków. She had survived the concentration camps, including the Płaszów concentration camp; Hedi and her husband emigrated to Palestine in 1946. From Emilia Ratz's Warsaw family the only survivor was her cousin Mieczysław Endler, who had escaped from the ghetto; using false papers he made his way to the USSR, where he joined the Anders Army; after the war he returned to Poland, but in the early 1950s he fled the country for the West.

In June 1946, Emilia Ratz gave birth to a son, Aleksander; due to malnutrition, both had serious health problems. Marcin Ratz worked at an enamelware factory at that time, Emilia Ratz became chief engineer at a cannery in 1947. Despite pressure from the authorities, the Ratz family did not change their surname to a Polish-sounding one (Raczyński or Rakowski were suggested). In 1949, Macin Ratz took up a job at Fabryka Samochodów Osobowych (FSO) and soon the whole family moved to Warsaw. In 1952, they had a daughter, Małgorzata, and Emilia Ratz joined the State Economic Planning Commission. After the outbreak of the Six-Day War in Israel, she was deprived of her post, arguing that she had a sister-in-law in a hostile state; she took another job as a technical advisor in a bank. The rise of anti-Semitic sentiment, however, led the Ratzes to seek to leave. Marcin Ratz, whose first language was German, decided to settle in Vienna, the city of his youthful education. He received permission for himself and his children to leave Poland, but Emilia Ratz, due to her jobs being covered by "secret information", had to wait another two years.

Eventually, the Ratz family made a life for themselves in Vienna. The wife earned a living as a technical translator, while her husband worked as a representative for a company producing pneumatic systems. He died in 1989, Emilia Ratz in 2015.

Ewa Małkowska-Bieniek, Przemysław Kaniecki

Znaleziono 54 obiektów

1931 — 1935

National Museum in Szczecin

1931 — 1951

National Museum in Lublin

20th century

Castle Museum in Łańcut

DISCOVER this TOPIC

Castle Museum in Łańcut

DISCOVER this PATH

Educational path