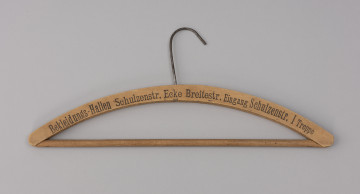

Summer dress by DANA

1967 — 1989

National Museum in Szczecin

For centuries, what was worn was primarily a testimony to the position that a person occupied in society - clothing was treated as a message to others. So what did the costumes say about their owners, from the 17th century to the beginning of the 20th century? It's time to take a closer look at it.

The bourgeoisie – a social group that emerged in the Middle Ages - lived in cities and was subject to municipal law. The townspeople were mostly traders and craftsmen. From the nineteenth century, the term "bourgeoisie" was used to describe all city dwellers or - less frequently - the wealthiest.

Netherlands – The historic name for the North Sea area that includes what is today Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Nobility – in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth it was a social group that enjoyed many privileges. A nobleman, i.e. a representative of the nobility, owned the land, and his children could inherit it from him. His high position was evidenced by the fact that he participated in the election of the ruler.

Znaleziono 0 obiektów

1967 — 1989

National Museum in Szczecin

1900 — 1945

National Museum in Szczecin

20th century

Castle Museum in Łańcut

DISCOVER this TOPIC

Castle Museum in Łańcut

DISCOVER this PATH

Educational path